Interview with Paul Northfield

Wednesday, October 28th, 2009 | by matthew mcglynn

Progressive rock fans need not look far to find Paul Northfield’s name among their music collections. Over the past 35 years, he has recorded Gentle Giant, RUSH, Asia, Queensrÿche, Porcupine Tree, and Dream Theater, along with dozens of other artists you know — like Steve Vai, Bryan Adams, Pat Travers, Hole, Ozzy, Judas Priest, Suicidal Tendencies, Marilyn Manson, and on and on and on.

Progressive rock fans need not look far to find Paul Northfield’s name among their music collections. Over the past 35 years, he has recorded Gentle Giant, RUSH, Asia, Queensrÿche, Porcupine Tree, and Dream Theater, along with dozens of other artists you know — like Steve Vai, Bryan Adams, Pat Travers, Hole, Ozzy, Judas Priest, Suicidal Tendencies, Marilyn Manson, and on and on and on.

At one time or another I’ve owned a major chunk of his discography. But more significant to me than the impressive breadth of his resume is the handful of standout records he has helped make. In other words, if I were stranded on the proverbial desert island, a couple of Northfield’s albums had better be there with me.

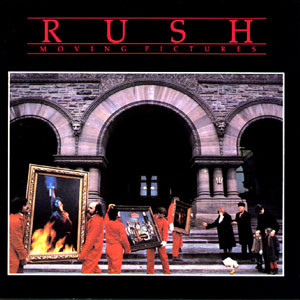

Say, for example, Moving Pictures. I know every note of that record. If I had a dollar for every time I’ve played it, I could buy my own desert island.

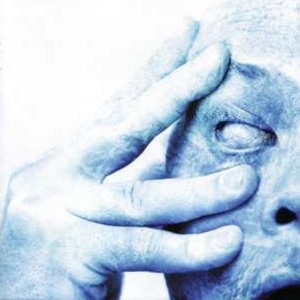

Or how about In Absentia? The first time I heard it, I caught myself sitting slackjawed at my desk. And then scrabbling for the liner notes to figure out where this amazing record came from.

It’s too soon to say for sure, but it seems that Dream Theater’s newest, Black Clouds and Silver Linings, would also make the short list. It’s getting a ton of airplay around here lately, to the point that my 4-year-old son can sing along to “The Count of Tuscany” (to my wife’s dismay).

I caught up with Paul earlier this year, after he’d returned home from a couple months in the studio with Dream Theater. We got deep into DT and RUSH, drum tracking, vintage gear, the state of the industry, and of course microphones. Here we go:

You first worked with Rush on Permanent Waves, around 1979. How did that come about?#

I started off at the age of 17 at Advision studios in London, as a tape op. Some of my favorite bands worked there; Yes and Emerson, Lake and Palmer, and so that’s what drew me to the studio. I worked in London for about five years. Then I was 22, and I was independent. I’d been working with Gentle Giant, and they brought me to work at Le Studio, which is in the mountains north of Montreal.

At that time, the studio scene wasn’t driven by independent engineers. There were a lot of independent producers, but, quite a lot of the time, you’d use in-house engineers because every studio was different. Every one had a sound and a specialization, so that people tended to go to a studio, and more than 50% of the time they would use the house engineers. As time went on, the engineering became more of a an independent enterprise, especially with standardization of consoles and monitoring, SSLs becoming ubiquitous, along with NS10s and such like.

So that brought me to Morin Heights. And they asked me if I would join the studio, so I ultimately did because being freelance was kind of hair-raising. And then Rush happened to be one of the clients that were interested in recording there, because it was a spectacular residential facility — in the mountains, with its own private lake. The studio overlooked the lake, and it was one of the few studios with large windows looking out. It was a wonderful environment to record in.

So I ended up engineering Permanent Waves. Terry Brown, at that point, had always engineered and produced the band, and this was the first time that he sat back and just did production.

Can you compare what it was like to work on Permanent Waves versus Vapor Trails, 22 years later? What was the same, and what was different?#

People look back on the ’70s and think “How did you do that? What special techniques did you use?” Often, pretty much everybody was just making it up as they went along. Recording was evolving at such a rapid rate, and studios were so different, fundamentally, from one to another. Now you can look across the history of recording and be very clear about saying “These are great microphones, these are great preamps…” We’ve now sort of analyzed it to death, to the point where we all have a consensus view of what stuff is great.

When we were working on Permanent Waves and Moving Pictures, the rooms were not as live. The general approach at that time was that you deadened everything down and then added reverb. That gave you more control. And it wasn’t until about five years after that, that we started to come across extraordinary sounding drum rooms.

RUSH always wanted to record things differently each time. It drove me nuts.

In the case of Rush, their own experimental eccentricity was that they always wanted to record things differently each time. It drove me nuts. We’d get a drum sound and then, after we’d recorded a song, they’d say, “Ok, well, that sounded great, so what mic shall we use on this next song?” It took a while to convince them — a couple of albums, actually! — to convince them that a lot more sound change would come from performance and the way something sits in an arrangement, than changing mics for change’s sake.

It’s hard to believe that, when you listen to Moving Pictures and Permanent Waves, that there’s very rarely two songs that have the same mics on the drum kit. I mean, the tom mics might have stayed the same for most of the time, but the kick drum mic would be changed all the time, and yet you wouldn’t necessarily know, because you always end up kind of re-EQing and fiddling. Which kind of gives you an idea that the thing that gives things consistency, with recording drums, has more to do with the nature of the room and the player, and the way his kit is tuned.

There are almost no mics that I used on recording Moving Pictures, for instance, that I would now currently choose. If I remember rightly, we tended to use things like U87s on the toms — it’s quite expensive if you hit them! Now I would pretty much always just turn to a 421, because 421s are a great tom mic, they’re robust; there’s lots of other great mics out there and some small condenser mics often, if you want them, but, even though I’ve experimented using 87s, since then, just for fun, I always turn away from them.

There are almost no mics that I used on recording Moving Pictures, for instance, that I would now currently choose. If I remember rightly, we tended to use things like U87s on the toms — it’s quite expensive if you hit them! Now I would pretty much always just turn to a 421, because 421s are a great tom mic, they’re robust; there’s lots of other great mics out there and some small condenser mics often, if you want them, but, even though I’ve experimented using 87s, since then, just for fun, I always turn away from them.

I wouldn’t choose to use old A80s to record on, even though they’re a great tape machine, and I certainly wouldn’t mix something down to a 16-bit Sony Digital machine, like we did with Moving Pictures. As good as Moving Pictures sounds, it was mixed onto what would now be regarded as a horrible digital stereo machine. Which just goes to show that it’s not always just about the gear.

It’s not always just about the gear.

At the time of Permanent Waves, Rush were a relatively young band, sort of experimenting and cutting their own path doing progressive rock. We set [them] up where everybody often would set up. Neil’s got a big kit, we set him up with his back to the window, overlooking the lake, in the part of the room with a higher ceiling. It’s only a three-piece [band], so we were not necessarily going to keep everything that they did on a live tape — we’d re-record the guitars and the bass, so we got two isolation booths. We recorded them like that, so that we could re-cut guitar and bass, which I think we probably did on almost everything. We would have recorded the drums, recorded bed tracks, sometimes with a click, often without, and then edit them together, to edit three or four takes together to make a song.

The difference between that and Vapor Trails was that Vapor Trails was a particularly complex record, for a lot of reasons. Neil Peart had just gone through a personal tragedy where he had lost his family, and the band had not actually recorded together for about three years. Neil had gone through a period where he didn’t play drums for about 18 months; he didn’t pick up a set of sticks, and at one point was not even sure if he ever would play again. But, after a certain period of time, he sort of felt an urge to just play a bit, and I remember him booking in at Morin Heights Studio under a pseudonym. So probably about 18 months or two years after having never had played drums to any degree or at all, he decided to do a bit of drumming, and decided it felt good, and then, as time went on, he got remarried which energized him, and then there was a discussion that they might do a record.

So there was a huge amount of psychological baggage involved in recording Vapor Trails, and I walked into that. Geddy and Alex had both done solo albums at that point. I was dealing with three individuals, as opposed to a band.

There was a certain kind of apprehension on Neil’s part, and Geddy and Alex’s parts about how comfortable everybody would be, and how Neil was going to feel. Even though Neil had been working a lot, you don’t stop playing for two years and then come back into it at the same level; as he said, “It takes a long time to build up the calluses.” And there was the fact that they’d been doing projects with other people, and this was the first time they’d recorded together after spending a couple of years apart, so it was a very different environment.

Geddy and Alex had done writing demos using Logic, so the tempos were all established, and a lot of very interesting arrangements done, sometimes some very interesting performances. The way that they would write is Geddy and Alex would kind of jam around a programmed drum part, and then structure a song in Logic. When I came to work with them on the album, we took the writing demos and rebuilt everything around those. We fine-tuned the demos in case there were any structural things we wanted to change, and then cut drums over them.

To get back to your original question about how differently we recorded it, that was probably the single largest thing that changed — [recording] drums over pre-recorded demos. The advantage to that is you can spin it back and punch in the drums, and Neil can have something that’s very consistent. He can rehearse to it, and it’s not going to change when he sits down in the room, as opposed to playing live with everybody where somebody pulls this way, somebody pulls that way. They’d arrived at that way of working 20 years between Permanent Waves and Vapor Trails.

So Neil liked to overdub drums to a guide track, and then they’d recap the guitars, and recap bass, and put the vocals on. In the past, most of the time nothing would be used from the demo. In this case, because the demos were done on Logic and [were] quite sophisticated, there were interesting things that were worth keeping, so we did keep some interesting guitar parts.

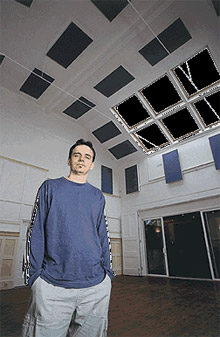

The other thing we did was use the studio that they were comfortable with. When I first started working on it, they wondered whether they wanted to stay at the same studio [Reaction Studios in Toronto]. It was convenient from their families’ point of view, and it was the place where they had spent the time writing, but it wasn’t a very live room. They really preferred the idea of just carrying on in the same studio, so I had the studio just tear out all of the deadening in the ceiling, and put drywall almost in the entire studio, which gave it a lot more of a live feel. It didn’t necessarily turn it into the best drum room I’ve ever been in, but it certainly gave us a very satisfactory result at the time, so we were quite comfortable. That was a rare occasion, that I literally changed the entire sound of the room to make it make sense. I wouldn’t normally choose to do that, I’d rather just go to a room that sounds like I want it to sound.

What makes a good drum room?#

The majority of the time, you want a relatively high ceiling. I’m not comfortable with a ceiling that’s less than about 10 feet, I prefer to be in a room that has a 12 foot to 20 foot ceiling, because then the cymbal splash is less irritating. If you were in a low ceilinged room playing rock, and somebody wails on the cymbals, it’s just going to be everywhere, bleeding into everything. To me, a great drum room is a room that’s live, but live more in the low end than in the top end.

If you’ve got a room that’s very brittle, with a lot of glass and tile, then the cymbal spill will be atrocious. That’s why drywall is actually quite a good surface for a room because it’s not too aggressively reflective for cymbals, especially if you’ve got a room that’s fairly large.

My ideal room for drums would be about 30 feet wide, 20 feet deep with a 16 foot ceiling, that was fundamentally live, but not brittle. Often the sound of the band on stage is actually quite a good one because you get a bit more weight from the kick drum and the toms because of the resonance that comes off of the floor. A room like Bearsville, which was a great drum room, had almost like a gymnasium floor. It has a bit of bounce to it, and if you bang your foot on it, you’ve got some sound there. It’s not just a hard concrete with wood on top of it. Those rooms I find quite interesting.

It’s very easy to deaden the area up around the drum kit; that’s another thing I sometimes like to do. If I’m in a very live room, then I’ll put gobos around the kit that make it quite dry in close proximity to the kit, which means that your close mics will sound close, but then the upper part of the kit has a lot of room to breathe, and if you put a few mics back in the room, you’ll still get a lot of room sound. So you’ll have a big contrast between the close mics and the room mics, which is actually quite fun, because then you have a lot more control.

If you’ve heard a drum kit played in a really great recording room, it’s very clear you can’t EQ that [sound] into it, if you’re in a room with carpets on the wall.

Let’s switch gears to talk about Dream Theater. You joined Dream Theater to engineer Systematic Chaos. They were coming off of a long run of working with Doug Oberkircher. What sort of change were they looking to make?#

They’d had Doug, who’d had always recorded their stuff, and then they’d used somebody else to mix everything. When they came to me, they were looking for somebody that they could have do everything. Aside from the stimulus of working with somebody new, they wanted somebody that they felt could mix the record as well.

They said “We’re going to write in the studio, so how do you feel about coming into the studio and you’ll be busy for, like, a week, setting everything up and then you’ll be sitting around a lot. Are you OK with that?”

![]() I was quite comfortable with the whole idea. I liked the idea of working with them because of the experimental nature of their music and, as much as I like to move quickly and efficiently when I’m recording, their reasons for being indulgent about writing and recording in the studio, as opposed to demoing and walking in and then being super efficient and cutting the drum tracks in a week or ten days and then moving on… I understood exactly where they were coming from, and I admired them for that choice. They don’t want to go through the process of spending a month or two writing and making a demo whilst they’re inspired with a song, and then going into the studio and then redoing it all. They just wanted to be inspired, get some ideas, record them, that’s it. Do a song, finish it.

I was quite comfortable with the whole idea. I liked the idea of working with them because of the experimental nature of their music and, as much as I like to move quickly and efficiently when I’m recording, their reasons for being indulgent about writing and recording in the studio, as opposed to demoing and walking in and then being super efficient and cutting the drum tracks in a week or ten days and then moving on… I understood exactly where they were coming from, and I admired them for that choice. They don’t want to go through the process of spending a month or two writing and making a demo whilst they’re inspired with a song, and then going into the studio and then redoing it all. They just wanted to be inspired, get some ideas, record them, that’s it. Do a song, finish it.

We’d do the drums, guitar, bass and sometimes some keyboard, and then move on to the next song. So we usually had finished the guitar work on a song — not the solo perhaps, but all the rhythm guitars — before we started on another song. That was their mode of working and that’s what brought us together to work on Systematic Chaos.

Did your role change at all for Black Clouds and Silver Linings?#

From the start, they said “Look, we’re producing the record ourselves, because we always know what we want to do. We wouldn’t mind some help with producing the vocals because it’s good for us to be able to sit back and have somebody else deal with that, and then us give some general direction about where we want to go.” So, on both records, I was involved in producing the vocals.

This time around — even though I’m not a credited producer apart from the vocals on the record — this time around there was more dialogue about what work they were more interested in. Mike and John are still the producers on the record, but, producing being what it is, everybody’s opinion is taken into consideration in some way. I think, perhaps, there was less tip-toeing around because they knew me and I knew them… if you had a criticism or a suggestion, you could more openly voice your opinion because everybody knew where everybody stood.

The Black Clouds album has the 5th and final song of Mike Portnoy’s epic “Twelve-Step Suite” of songs about recovery from alcoholism. How did that go down?#

They used elements of all of the previous sections that they’d written. Mike comes in with lyrical content in mind, and that gives it structure. He doesn’t come in with a completely written piece; it’s more like film directing. He comes in with a vision or an image, or a sentiment that this is going to be about. This one was more defined, in the sense that he wanted to borrow elements, take elements from the earlier parts and use those in different ways in this song. Aside from writing new parts for it, he wanted to be able to use some of the theme, and I think that really worked quite effectively, without it sounding like just a medley of other ideas. Some of the melodic themes and stuff like that are reused in different ways. So, in that sense, that was a sort of defining characteristic of this final piece, just so it ties them together. At some point they’re talking about performing it as a whole on stage.

Let’s talk about tracking drums. You’ve worked with three of my favorite drummers — Mike Portnoy being one, Gavin Harrison is another, and of course Neil Peart. They all have a ton of experience recording. Do these three — and maybe there are different answers — but do these drummers come in with specific ideas about engineering? Such as microphone choice, placement, technique?#

I can answer that one very clearly: No. Absolutely not. They are not really interested in how you achieve what you achieve.

Neil Peart, from day one, had his drum kit sounding the way he wanted it to sound. Neil was difficult to record in the early days, particularly, because we had more dry, or deader rooms, and his snare drum in particular was tuned very high. It would probably sound incredible live because it would speak in an ambient environment really well, but, in a drier room, it was quite hard work. All you got on a close mic would be a clicking sound, very tight. Not high and ringy, but very tight. But he hit it so hard that when you stood back from it, it was very, very powerful. But, if you didn’t have a room that really sounded great with your just ambient mics, your close mic tended to be very tight and constrained. That was the hardest thing about recording Neil’s kit, but everything else about it was very easy, his toms always sounded great.

On one occasion we said, “Neil, do you think you could tune this snare drum down a bit, because we could do with it a bit fatter.” He said, “It sounds exactly the way I like it right here!” So it was like the gauntlet was thrown down — “I’m doing what I like, what I want; you make it sound good.” That established very clearly the nature of the relationship.

People love the way Moving Pictures sounds, and I’m very proud of it as a record, but the hardest thing with recording Neil was his snare drum sound. It sounds great, but it was hard work.

But back to your question… Neil was very specific that his kit sounded the way he wanted it. You just record it.

In the case of Gavin, he had a really nice drum recording room at his house in England. When I worked with him with Porcupine Tree [on In Absentia], he’d not worked with the band before. He was coming into the band as a session drummer with a view to possibly joining the band, depending on how everything went. So, other than listening to some demos, I think, and discussions, I don’t even know if they’d actually ever played together. I think he just listened to some demos of Steve [Wilson]’s.

In the case of Gavin, he had a really nice drum recording room at his house in England. When I worked with him with Porcupine Tree [on In Absentia], he’d not worked with the band before. He was coming into the band as a session drummer with a view to possibly joining the band, depending on how everything went. So, other than listening to some demos, I think, and discussions, I don’t even know if they’d actually ever played together. I think he just listened to some demos of Steve [Wilson]’s.

I chose to work at Avatar, because they wanted to record in New York. It was what was formerly the Power Station, and had a great drum room — a lot of wood and a nice, high ceiling and a classic old Neve console to track on. Gavin came in as a session drummer to cut tracks, and it just goes to show what an extraordinary drummer he is that he could be so musically sensitive and expressive just coming in to play on something that was already pre-existing. I think Gavin just had a kit brought in that was similar to his. I think he didn’t have his own kit with him.

Since that time, Steve has recorded Gavin himself at Gavin’s house, because obviously it’s much more cost efficient, and Steve is a very talented producer/engineer in his own right. [Gavin contacted us with a minor correction; he actually does all his own tracking at home. Steve Wilson described the process in the current issue of Tape Op: “Gavin has spent years experimenting in his own studio with mics and preamps, and he now has a system that he’s perfected. I don’t need to sit there with him while he’s recording his drum parts.” –Ed.]

Since that time, Steve has recorded Gavin himself at Gavin’s house, because obviously it’s much more cost efficient, and Steve is a very talented producer/engineer in his own right. [Gavin contacted us with a minor correction; he actually does all his own tracking at home. Steve Wilson described the process in the current issue of Tape Op: “Gavin has spent years experimenting in his own studio with mics and preamps, and he now has a system that he’s perfected. I don’t need to sit there with him while he’s recording his drum parts.” –Ed.]

As for Mike, he is so involved in the production and the vision and the ideas of Dream Theater that he’s not particularly interested in what’s involved in recording them, even to the extent that he would prefer that somebody else gets the sound. He says, “You guys take care of all that — I want to be able to sit down and play.”

Mike has a great drum tech [Eric Disrude — who we’re trying to contact for an upcoming feature], who can tune the drums, and who knows Mike, knows what he wants, can set the kit up the way he wants, and then can play it well enough for me to be able to dial it in.

How has drum recording changed in the past 20 years?#

20 years ago you’d take a drum kit like that and record it on seven or eight tracks. Now, tracks are unlimited, so it’s very easy just to put one mic on one drum on one track. That means I’ve got, in the case of Mike, 20 or 30 tracks for the drums — I’ve got a microphone going from every drum to a separate track on the multitrack.

When I used to do early Rush, the entire seven toms would always be mixed as a stereo pair. We’d have a stereo pair of toms, a stereo overhead, kick drum, snare drum, high hat… right there you’ve got seven tracks to record on, maybe a couple of extra tracks for ambiance if there was interesting ambiance.

But now you can leave [mixing] decisions till later. You can record every drum to a separate track, and that way, if the drummer didn’t chose to play some, I don’t have to have open mics. I’ve never been a fan of gating everything. Often you want the resonance of the open tom mics that sort of fill out the sound. But there might be one tom that’s really annoying and rings, so you want to be able to mute it. Now, instead of having to know when he’s going to play the 13 inch rack tom that always rings when he hits the snare, you can just not worry about it and deal with it afterwards. When we were mixing everything down [to stereo during tracking], then maybe we would use some gating on a particularly difficult drum.

When I’m mixing, I open up and see which tom mics actually add to the sound of the kit.

As an engineer, do you get into specific recommendations to the drummer regarding drum tuning and head choices?#

If the drummer you’re dealing with has a very defined sound, and the drum tech knows what the drummer is going to like, you’d start from that basis. Then you’d go back and look and say “Ok, this is working for me” or “we’ve got a problem with this or that.”

Usually it revolves around something like where the pitch of the kick drum would be tuned — or invariably, with a large kit, you’ll find a bunch of toms that sound great, and there will be one or two that are kind of clunky. Or, when they’re tuned at the pitch that you kind of want them to be, one will have a weird resonance to it. So you have to deal with that.

What’s your preferred gear for tracking drums?#

If I’m going to be in an SSL room and I’m tracking, then I’m going to need a lot of output gear, a lot of Neves to track drums through. That’s particularly true of a E series; there’s not many people you’ll find who record on an E series. Even though I recorded Moving Pictures on an E series, we had two Neve mic pres on the little console we had. We had a kick drum Neve channel and a snare drum Neve channel.

Permanent Waves it was all recorded on a Trident A series console, but, in later recording, whenever I’m recording anything, I’ve invariably got a rack of Neves to do kicks, snare and toms, for sure. If I’m lucky and I’m on a great classic old Neve console, then, right away the palette that you’re dealing with is a lot thicker and weightier, and you don’t find yourself having to EQ a lot of stuff into it.

Mike Portnoy’s drum-cam videos [sample trailer] show that each song is comprised of many different drum takes and overdubs. How do you manage that process? And more generally, how did the band approach the tracking for the two latest records?#

The fundamental way that we approached both Systematic Chaos and the new one is that guide tracks were laid down — after they’d written the song, they would map out the optimum tempo for each section, and we would make a click track. In the case of Systematic Chaos they would just play all together against a click track that had programmed tempo and meter changes. They’d play a take to something like that and, as long as it was a pretty good take, Mike would use that as his reference, and listen mostly to the click, and keep the other instruments just sort of loud enough so he knows where he is. So when you see his live studio cams, he’s playing to a click with guide tracks.

It used to drive them insane how long it would take to program a click that felt comfortable to play to. They’d have recorded the demo just playing freeform, and then sit and discuss it. And they’d play it again together and say “Ok, no, let’s go two or three beats per minute faster…” They’d spent a day just trying to get a click track that felt comfortable for a 10-15 minute song, and it was extremely tedious and they hated doing it, but they knew this was the only way they could comfortably end up with something that moved from section to section in the way that they wanted.

This time around, we used technology to our advantage. They played the pieces as they liked. I recorded the songs into Pro Tools, then I created a click track absolutely precisely locked to the live performances, and then used the Elastic Time function in Pro Tools to remove any tempo changes that were not liked. If the band said, “We want the bridge two beats per minute faster,” I could just adjust that, and all of the tracks, the guide drums, everything, would just be time-stretched, using Elastic Time.

What that meant was that, first of all, they didn’t have to spend hours tediously doing it themselves. They could just listen to it and say “Oh, we like it two beats per minute faster,” instead of having to discuss it, experiment, play it together, record it again. They could just all sit in the control room — well, Mike or John for the most part — and listen, and I can just adjust it on the fly. Once it was all settled, what we ended up with was a track that was sometimes untouched because they played the song very steadily, other places where it’s within one beat per minute, because we’d removed all the little changes that might have happened, and still other places where there are some natural tempo changes in this recording that are actual live drum performances.

With a drummer like Mike, some of his spontaneous performances are extraordinary, so there were a couple of occasions where we used the original demo drum performance for a certain section of the song. Usually I’d re-record him three times through a song. And then we would sit down together and decide which are the best takes, and edit them together. If there’s something missing, like a drum fill here or there, or he’s decided that he wants to play a different feel — usually it will be something like “I want to play that on the ride, not on the hi-hat” — then he’ll go back in and punch them in.

So what is the process, actually, when you have maybe three takes plus the demo? How do you aggregate those into a final track? Is Mike Portnoy sitting next to you at the console?#

Well, yeah. Basically, Mike will come in and listen and take notes. He basically decides what he was wanting to do, and I have some input because he likes to ask me what I think, so, for the most part, we sit and discuss. I’ll tell him which I thought was the best performance, and he knows what he’s looking for — sometimes we have different things that are of concern, so, between the two of us, we arrive at a point where he’ll say “Ok, the good drum take will be this one up to the first chorus, and then this take is really good on the chorus.” You might end up with almost one take for the entire song. But that’s basically it, we’ll just sit together and decide together which ones we’re going to use and then they’re just edited [with] playlist editing in Pro Tools.

[We got into some nitty-gritty drum editing details with Mr. Northfield, which we’ve reserved for a future article.]

Let’s talk about technique, and about learning how to record. A lot of magazines use a lot of ink dissecting how particular engineers like to work…#

One of the things I used to chuckle about was when MIX Magazine first came out, they always used to have layout pictures of the drum kits and where the mics were, and I always used to find that quite amusing because, in reality, the mics are always in essentially the same places, and the drums are always laid out in essentially the same way, and what you can glean from that information is not that useful. It’s like, ok, the mics are on top of the skins just slightly in from the rim… they’re almost always in that spot, because it’s the convenient spot.

There are techniques that you can use that are interesting. For example, double miking [toms from] top and bottom with a phase flip [on the bottom mic] — that’s a technique that some people have used. That would be something that would be interesting to talk about. But, very often, what happens is that when someone makes a quintessential recording that everybody else regards as brilliant, then we’d try to deconstruct it. But if I were put in the same situation, with the same drummer, with the same room, the likelihood of me making it sound the same is very slim. And when you take the fact that, if somebody is not in the same room, without the same console, and you’ve got a different drummer with different drums trying to make something sound like that, it’s not going to be easy.

So, consequently, when you draw out on a piece of paper the way those things are, it really misses the point.

If I would try to deconstruct Moving Pictures, which I would say is an important piece of work in my career, I would say, “Well, we had a bunch of different gear that I would never use now, but it sounded good.” Why did it sound good? Some of it was because of it being a particular time in Rush’s evolution; they were playing a certain style, they’d evolved in their playing, in their arrangements. The studio and the recording technology was interesting; there was some really good new technology, and some great classic stuff, but the digital technology was terrible. But we had a lot of great analog [gear] that balanced it out. At the end of the day, it’s all subjective — like, whatever gear we had is what we had, good or bad, and we used our taste to make it sound good.

I understand from your point of view that’s not very helpful. I understand the desire to write down details, which is why I tried to talk a little bit about the way rooms are, and the way consoles are, and things like that. Because they’re big palate issues. There is a huge difference between recording a drum kit on a Neve and recording it on an old E series SSL. And I would never record Neil Peart on an old E series SSL… except Moving Pictures was recorded on an old E series! And it was lucky that we managed to achieve the results that we did.

I’m contractually obligated to ask you about microphones. Well, not really. But do you have any secret go-to inexpensive favorites?#

I don’t get to play with some of the oddball cheap ones, that are like a real surprise, ’cause when you are given a choice, well, you can have a C12 or some oddball microphone, you just say “Oh, ok, we’ll just put the C12 on.”

I don’t get to play with some of the oddball cheap ones, that are like a real surprise, ’cause when you are given a choice, well, you can have a C12 or some oddball microphone, you just say “Oh, ok, we’ll just put the C12 on.”

My favorite less-expensive microphones are the Blue microphones, some of which are actually very expensive, but the cheaper ones they have are really amazing too. The Blueberry! I think that is a wonderful microphone. At Avatar, we had it twice in a room side by side with two C24s, but we used the Blueberry instead.

My favorite less-expensive microphones are the Blue microphones, some of which are actually very expensive, but the cheaper ones they have are really amazing too. The Blueberry! I think that is a wonderful microphone. At Avatar, we had it twice in a room side by side with two C24s, but we used the Blueberry instead.

My vocal mic of choice, that I carried around for years, was a Sanken CU41, which is a $3,000 microphone. It invariably sounded great. I used it with Geoff Tate originally, on [Queensrÿche’s] Operation: Mindcrime; it became a favorite because it could take a lot of level when he was singing up close to it. It has a [dual] capsule with a high frequency and low frequency module inside and it’s one of the few that exists like that, where it’s actually got to have a crossover in it. It’s a great microphone and I used that for years with Suicidal Tendencies, I used it on Ozzie, I think, at one point, and I used it on Alice Cooper records, so I had one of those myself. But I’m now very tempted to go out and get a Blueberry.

My vocal mic of choice, that I carried around for years, was a Sanken CU41, which is a $3,000 microphone. It invariably sounded great. I used it with Geoff Tate originally, on [Queensrÿche’s] Operation: Mindcrime; it became a favorite because it could take a lot of level when he was singing up close to it. It has a [dual] capsule with a high frequency and low frequency module inside and it’s one of the few that exists like that, where it’s actually got to have a crossover in it. It’s a great microphone and I used that for years with Suicidal Tendencies, I used it on Ozzie, I think, at one point, and I used it on Alice Cooper records, so I had one of those myself. But I’m now very tempted to go out and get a Blueberry.

The C24 has a double capsule, which you can rotate, so, basically, it’s like having two C12s in one mic. You can choose whether you want to use the top or the bottom capsule. But, invariably, the main criticism of those old tube mics was that they were inconsistent. I’ve heard C12s that were radically different from each other, in some of which the top end is spectacular and glorious for cymbals and stuff like that, and others where it’s actually quite coarse — it’s a very different sounding microphone altogether. People tend to remember the ones that sound amazing.

The C24 has a double capsule, which you can rotate, so, basically, it’s like having two C12s in one mic. You can choose whether you want to use the top or the bottom capsule. But, invariably, the main criticism of those old tube mics was that they were inconsistent. I’ve heard C12s that were radically different from each other, in some of which the top end is spectacular and glorious for cymbals and stuff like that, and others where it’s actually quite coarse — it’s a very different sounding microphone altogether. People tend to remember the ones that sound amazing.

Actually, that’s one of the things that we didn’t touch on. A large part of recording is rediscovering other things that were commonplace years ago, that nobody used to talk about, that now everybody wants to use all the time. Neve would be a classic case in point. In the early days, you were listening to stuff on big soffit mounted speakers with three or four [drivers], sometimes JBLs, which were more like a dance PA than a high resolution speaker. You were recording it onto a tape machine, which may or may not have significant distortion — it could be something as different as an MCI JH-24, or a Studer 800, or a Studer A80, or an Ampex 2, which have very different sonic characteristics, equally as dramatic, sonically, as the console is itself. And if you were mixing through the whole system again, and mixing onto tape, you were always fighting against the thickness and the mud that analog distortion tended to bring, like analog distortion fuzzing things up a bit, tons of transformers making it thick and resonant, all of those things. So, when you [later] got equipment that was very clear, like transformerless equipment, you tended to gravitate towards it.

Actually, that’s one of the things that we didn’t touch on. A large part of recording is rediscovering other things that were commonplace years ago, that nobody used to talk about, that now everybody wants to use all the time. Neve would be a classic case in point. In the early days, you were listening to stuff on big soffit mounted speakers with three or four [drivers], sometimes JBLs, which were more like a dance PA than a high resolution speaker. You were recording it onto a tape machine, which may or may not have significant distortion — it could be something as different as an MCI JH-24, or a Studer 800, or a Studer A80, or an Ampex 2, which have very different sonic characteristics, equally as dramatic, sonically, as the console is itself. And if you were mixing through the whole system again, and mixing onto tape, you were always fighting against the thickness and the mud that analog distortion tended to bring, like analog distortion fuzzing things up a bit, tons of transformers making it thick and resonant, all of those things. So, when you [later] got equipment that was very clear, like transformerless equipment, you tended to gravitate towards it.

Now we have tons of equipment that is very clear and with very little personality. The digital medium itself, when you’ve got all your levels right and you’ve got good converters, is very clear. It’s almost an invisible medium, and so what you look for [in outboard gear] is personality. The value of those harmonically interesting bits of equipment with lots of distortion and, sometimes, phase shift and, sometimes, harmonic distortion from transformers, becomes very interesting because you hear it in ways that, 30 years ago, when it was made, we never heard. We often used a Neve for recording and mixed through a Neve again, off of tape, through a pair of speakers that were like a PA. So it’s only as you step back a way, you suddenly start rediscovering things.

Are you a fan of vintage recordings?#

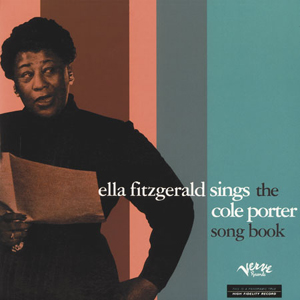

Listen to Rudy Van Gelder’s recordings, or get a copy of something like Ella Sings the Cole Porter Songbook, on Verve. It’s really worth having in your collection. What’s incredible about it is the beauty and clarity of the recording, when you consider that, at the time when they were doing this, they were probably listening through a pair of Altec 604s, or something like that. They couldn’t hear what they were doing! So how could it be that good? Well, the mics, obviously… Nobody was grabbing for EQs left, right and center. It was about extraordinary performances, recorded with extraordinary microphones, and not too much else in between.

Listen to Rudy Van Gelder’s recordings, or get a copy of something like Ella Sings the Cole Porter Songbook, on Verve. It’s really worth having in your collection. What’s incredible about it is the beauty and clarity of the recording, when you consider that, at the time when they were doing this, they were probably listening through a pair of Altec 604s, or something like that. They couldn’t hear what they were doing! So how could it be that good? Well, the mics, obviously… Nobody was grabbing for EQs left, right and center. It was about extraordinary performances, recorded with extraordinary microphones, and not too much else in between.

So now we’ve covered recording history from what were probably two- or three-track recordings of Ella Fitzgerald in the 1950s, to using 30 tracks for a drum kit in 2009! What’s your take on the state of recording now?#

At the moment, I almost feel like writing a book about recording — whether the golden era of recording has passed now, or whether it is yet to come. The reason I say that is that the aspect of the golden era that is hard to maintain is that whole dynamic of a specialized place where people come together to record. Like the Power Station, or Avatar. It was a classic in its time. During the day, you might be recording Bruce Springsteen and, at night, you might be recording Roxy Music. If you wanted to book a lockout, you had to pay for 24 hours, because they could book it with Roxy Music at night and Springsteen during the day. It was that busy.

What that meant was that you had this constant cross-fertilization of knowledge. And also there was a lot of money in it for the studios. That studio must have been making $4,000 to $5,000 a day on one room, 20 years ago. You can’t do that now.

Conversely, everybody with $10,000 in their pocket and a computer can set themselves up with a minimalist studio, [and] do incredible recordings. I’ve done quite a few situations like that. I did some stuff with Marilyn Manson — we built the studio in the old Houdini mansion in Los Angeles to record Holy Wood. It was just an empty building that was owned by Rick Rubin. The best room for a control room, for size, and shape and convenience was a room that had a white marble floor and dry wall. It sounded like a bathroom. But in the space of a week, we temporarily turned it into the control room. We spent about $30,000 on the set-up, but he was there for three or four months. It’s a different environment now, recording.

Conversely, everybody with $10,000 in their pocket and a computer can set themselves up with a minimalist studio, [and] do incredible recordings. I’ve done quite a few situations like that. I did some stuff with Marilyn Manson — we built the studio in the old Houdini mansion in Los Angeles to record Holy Wood. It was just an empty building that was owned by Rick Rubin. The best room for a control room, for size, and shape and convenience was a room that had a white marble floor and dry wall. It sounded like a bathroom. But in the space of a week, we temporarily turned it into the control room. We spent about $30,000 on the set-up, but he was there for three or four months. It’s a different environment now, recording.

There’s no longer really a business model for the recording industry.

It’s quite possible that some of the greatest work recording ever done will come in the future, but I have this feeling that the golden era is now past because there’s no longer really a business model for the recording industry. It’s not actually a business any more; it’s a love for some people. It doesn’t mean to say there’s no money to be made anywhere in it — if you have another reason to own a studio, you’re constantly busy or you have another source of income, then owning a studio might be financially viable. Beyond that, don’t expect to make much more money than the gear cost you.

A good example is Sunset Sound in Los Angeles. The last time I was there I was amazed at how well looked-after it was. There was no ostentatiousness about the studio at all, and yet it was up to date, there was a lot of effort put into it. But they said that the reason it’s still going is it is still owned by the original family, and if they wanted to make money, they would just tear it down and use it as a parking lot. Literally, use it as a parking lot. Because it would have probably brought in a couple of million bucks a year as a parking lot. As a studio it probably loses a few hundred thousand a year. Maybe the rise in the real estate [values] offset that… [maybe they’re thinking,] “our bank account looks better each year ’cause of how much our property’s worth, so we can afford to lose a couple of hundred thousand every year on a fully operational classic recording studio.” It’s a strange world now.

A good example is Sunset Sound in Los Angeles. The last time I was there I was amazed at how well looked-after it was. There was no ostentatiousness about the studio at all, and yet it was up to date, there was a lot of effort put into it. But they said that the reason it’s still going is it is still owned by the original family, and if they wanted to make money, they would just tear it down and use it as a parking lot. Literally, use it as a parking lot. Because it would have probably brought in a couple of million bucks a year as a parking lot. As a studio it probably loses a few hundred thousand a year. Maybe the rise in the real estate [values] offset that… [maybe they’re thinking,] “our bank account looks better each year ’cause of how much our property’s worth, so we can afford to lose a couple of hundred thousand every year on a fully operational classic recording studio.” It’s a strange world now.

Many thanks to Paul Northfield for graciously answering so many questions!

To submit questions for future interviews, follow me via Twitter. And be sure to grab an RSS feed on your way out… (top right corner of the page)

For more about recording Vapor Trails, check out MIX Magazine’s story. For more about recording Dream Theater, see Roberto Martinelli’s great interview with Portnoy, Northfield, and Eric Disrude. And finally, see Neil Peart’s DVD “Anatomy of a Drum Solo” has a fun video interview with Paul Northfield and Lorne Wheaton.

You did see the Microphone Database, right?

Tags: dream theater, gavin harrison, geoff tate, marilyn manson, mike portnoy, neil peart, paul northfield, porcupine tree, rush, terry brown

Posted in Interviews | 9 Comments »

Aaron Lyon

October 29th, 2009 at 6:52 am

Wow! Great interview, Matt. Except, gawd, all those questions about drums! I think there might have been some melodic musicians in those bands, too. Geez.

Joe Chellman

October 29th, 2009 at 7:25 am

Agreed, great interview. Thanks for that! And for the record, I’m quite happy with all the questions about the drummers, since that’s what I know and am most interested in.

Paul Northfield interview « Echoes of Pink Floyd

October 29th, 2009 at 1:59 pm

[…] http://recordinghacks.com/2009/10/28/paul-northfield/ Progressive rock fans need not look far to find Paul Northfield’s name among their music collections. Over the past 35 years, he has recorded Gentle Giant, RUSH, Asia, Queensrÿche, Porcupine Tree, and Dream Theater, along with dozens of other artists you know — like Steve Vai, Bryan Adams, Pat Travers, Hole, Ozzy, Judas Priest, Suicidal Tendencies, Marilyn Manson, and on and on and on. […]

Laurie Monk

October 30th, 2009 at 3:54 am

brilliant post! I want to thank you for the time and effort to get that together.

Andy Olson

October 30th, 2009 at 2:58 pm

Excellent interview with Mr. Northfield. Being a drummer and fan of Neil Peart and Rush, I’d often wondered about how they got such great sounds on “Permanent Waves” and “Moving Pictures.” Now I find out that they changed the drum mics for every song!

Babul A. Mukherjee

October 30th, 2009 at 8:15 pm

Wonderful interview! What an amazing career and very insightful. Thanks Paul for your work, especially with Rush. Your recordings have been and will continue to be part of my core.

Regis Chapman

November 1st, 2009 at 10:08 am

Awesome post and excellent in depth info for hardcore fans. I appreciate very much the work it took to assemble all this.

owen ross

November 10th, 2009 at 9:42 pm

Great article, i didn’t understand part of it (the technical aspect) but i’m a huge Rush fan so in was very informative. My only comment really is as great as Moving Pictures sounds, Vapor Trails just sounds horrible. I’m not in the minority here Rush themselves have rereleased remixed versions of 2 vapor trails songs this year. Here’s hoping they will remix the entire Vapor Trails cd for rerelease as well. The cd is loud, noisy and almost impossible to hear the individual instruments. Thanks for reading, and keep up the great interviews.

Paul Northfield Interview - Ultimate Metal Forum

January 4th, 2010 at 5:43 am

[…] Northfield Interview http://recordinghacks.com/2009/10/28/paul-northfield/ some pretty cool stuff in there, definitely a lot of stuff that I agree with and have learned to […]