Neumann Sennheiser Factory Tour

Thursday, August 2nd, 2012 | by matthew mcglynn

In early 2008, the RecordingHacks website was just two months old, more impressive for its promise than for what it actually delivered. Yet I flew my newly-minted “journalist” card to Wennebostel (near Hanover, Germany) to visit the Sennheiser/Neumann factory. The Sennheiser marketing staff responded enthusiastically, and I spent a day touring the facilities with the production manager for Neumann.

In early 2008, the RecordingHacks website was just two months old, more impressive for its promise than for what it actually delivered. Yet I flew my newly-minted “journalist” card to Wennebostel (near Hanover, Germany) to visit the Sennheiser/Neumann factory. The Sennheiser marketing staff responded enthusiastically, and I spent a day touring the facilities with the production manager for Neumann.

As a tourist, I’ve never been one for trudging through dusty museums and churches. But if ever someone writes a book on “100 places to see before you die (assuming you’re an audio nerd),” I think the Neumann factory will be near the top of the list.

I saw microphones in every state of construction from beginning to end, from the shaping of raw metal stock, to capsule milling, clean room operations, final assembly, and anechoic chamber testing. I actually got to sit inside an anechoic chamber while a U87 Ai was being tested — but more on that in a bit.

That day, I took a great many photographs, with the understanding that I would need to submit them for approval before publication, lest I reveal a supplier or process whose details would be detrimental to the company’s financial well-being. This exercise was as quick and predictable as the German train system. And yet I never published the story, nor the photos, until now…

The first thing we did was don lab coats, complete with Sennheiser logo. I was in no position to ask for souvenirs, but if I had been, I would have loved to take one of these home. (Assuming that a  Neumann U 87 Ai was off the table.)

Neumann U 87 Ai was off the table.)

CNC

The tour started in a warehouse-sized factory space, a long room lined on both sides with CNC machines, routers, drill presses, and more. We paused at a low table filled with samples of all the parts produced in this room: capsule backplates and mounts, microphone grilles, chassis, and headbaskets, and of course all manner of microphone bodies, for both Neumann and Sennheiser product lines.

|

|

|

Several components were in production at the time, with multiple CNCs (computerized metal shapers) grinding away inside their waterproof cabinets. Outside each one stood what looked like a dishwasher rack full of gleaming, hot-off-the-proverbial-press microphone parts.

|

|

|

|

Capsule Backplate Drilling

Midway down the line, I saw that the factory was also producing K67 capsules this day. The K67/K87 is the capsule in Neumann’s flagship condenser, the U87 Ai. Although I was asked not to publish any of my photos of the capsule machining process(es), I got approval for this image of a batch of capsule backplates in progress. Each of these backplates gets drilled on both sides, some holes going through, and some “blind” holes going only partway through the brass. Then the faces are “lapped” (polished). Later, the staff in the cleanroom fits and tensions a gold-coated Mylar diaphragm to one side of each backplate. These capsule halves are tested, paired, and mounted together to produce a single K67 capsule.

|

Shockmounts

We saw shockmounts in production as well — a remarkably manual process that probably has not changed in 50 years. Well, except for the glass-walled, fireproof, ventilated room that the 50-year-old manual process took place in.

Inside the booth, a single craftsman, clad in a heavy leather apron, hand-brazed shockmount cages together with a torch. He took pre-formed metal parts, set them into wooden forms to hold spacing and position, and welded them together to form shockmount cages. Bins of the resulting sub-assemblies sat in the hall, waiting their turn for sandblasting, polishing, and plating.

I admit to being astounded that these parts can’t be built by robots, or imported from somewhere with more favorable labor costs. So I asked the question: why not import these? The answer: the company felt that they couldn’t get the necessary quality at a lower cost anywhere else.

|

|

|

Headbaskets

Next up was the grille assembly area — just one more small piece of a big room, every workspace in which was stacked with pieces of microphones that you’d recognise.

U87 headbaskets are assembled mostly by hand, starting with a stack of three layers of metal mesh (one fine-mesh layer between two coarser layers). These are stacked, aligned, and press-formed into shape, to form the familiar sloped Neumann grille. Two sides are bound together inside a U-shaped bracket, then mounted to a ring to hold the whole thing together.

There is some manual TLC with small tools here, to make sure all the stray wire ends are tucked into place. Note the photos of the assembler; he’s wearing gloves to keep the metal surfaces clean.

Then the assembled pieces are fed one by one on glass pedestals on a turntable into a heat-treating station to set the solder (shown in the rear of the last photo below).

|

|

|

|

Cleanroom

Then we saw the cleanroom, where capsule assembly takes place.

What’s a cleanroom, and why did Sennheiser go to the expense to build one, given that some of their offshore competition assembles capsules right on the factory floor (he says with the voice of bitter experience following an ill-advised group buy of “cheap” microphones)?

In a typical condenser microphone capsule, the diaphragm is suspended 35–45 µm (microns) above the backplate. That distance is half the thickness of a human hair. Common atmospheric dust can measure up to 30 microns in diameter. Sawdust starts at 30 microns and can be much larger. If any of this junk gets trapped under the diaphragm, the capsule won’t sound right. The maximum diaphragm excursion on Neumann’s K47/K49 capsule, for any audio source short of a gunshot, is less than 1 micron. Clearly, if the factory would be cranking out capsules with crap trapped beneath the membrane, the resulting microphones will be severely compromised.

Sennheiser’s “Class 100” cleanroom allows a maximum of 100 tiny particles (0.5 micron ≤ x < 5 micron) per cubic meter of air. If that sounds like a lot, consider that an office building’s air is clogged with over 500,000 particles per cubic meter. (My home office has, no doubt, even more than that.)

Clean rooms often have positive internal air pressure, and/or airlock doors. The staff inside wears lint-free clothing and surgical-style hats. All so you can buy kick-ass, reliable, consistent microphones!

The room was idle during my visit (first photo), but I was able to get two PR shots from Sennheiser’s marketing team showing some of the assembly processes in action. (I can get more; leave a comment at the end of the piece if you are interested.)

|

|

|

|

Evolution

The next stop on the tour was the Evolution room.

Evolution is Sennheiser’s answer to the Shure Beta product line: affordable, rugged microphones intended for use on stage (although they all of course turn up in studios as well). The production process is highly automated. I watched in fascination as moving-coil cartridges came shooting out of some sort of assembly machine. A few, comically, had loose wires poking out or other obvious flaws; these were culled, and relegated unceremoniously to a plastic bin on the floor.

This facility presents a marked contrast to the Neumann assembly area, where a series of skilled craftspeople and engineers perform high-touch manual processes to complete a single premium microphone. My point is not that the Evolution microphones are sub-par at all — merely that there is necessarily a different production process for a $300 mic than a $3200 mic. The Evolution microphones are solid, rugged, consistent, and desirable, but they are not handbuilt. The anecdote above about rejected cartridges just illustrates the difference: rather than pay a small staff of experts to build perfection, with the Evolution line Sennheiser has (largely) automated a high-volume process, accepting that some percentage of the parts won’t meet spec, and still realized a sufficiently high yield of good parts to meet the product line’s affordable price points.

The sight of these things rolling off the production line by the hundreds, poked only occasionally by the machines’ human minders, was a bit unnerving. Machines building machines!

(To be fair, I’m sure there are manual steps in the manufacture of Evolution mics. I just didn’t see any during my visit.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Neumann Final Assembly

The final assembly area for Neumann was significantly quieter and slower paced. Here, capsule assemblies were mounted to electronics, mated to bodies and grills, inspected, tested, and packaged.

The first thing I noticed was a tall shelf unit with plastic bins labelled with the names of various U87 sub-assemblies. We went through them, just because I was fascinated with the idea that something I’d very much like to take home was stacked up in large quantitites. (I get much the same feeling when I tour breweries.) Pictured are the U87’s capsule mount, its K67 capsule, the chassis with PCB, and a freshly built, complete U87, bound for the anechoic chamber.

|

|

|

|

|

|

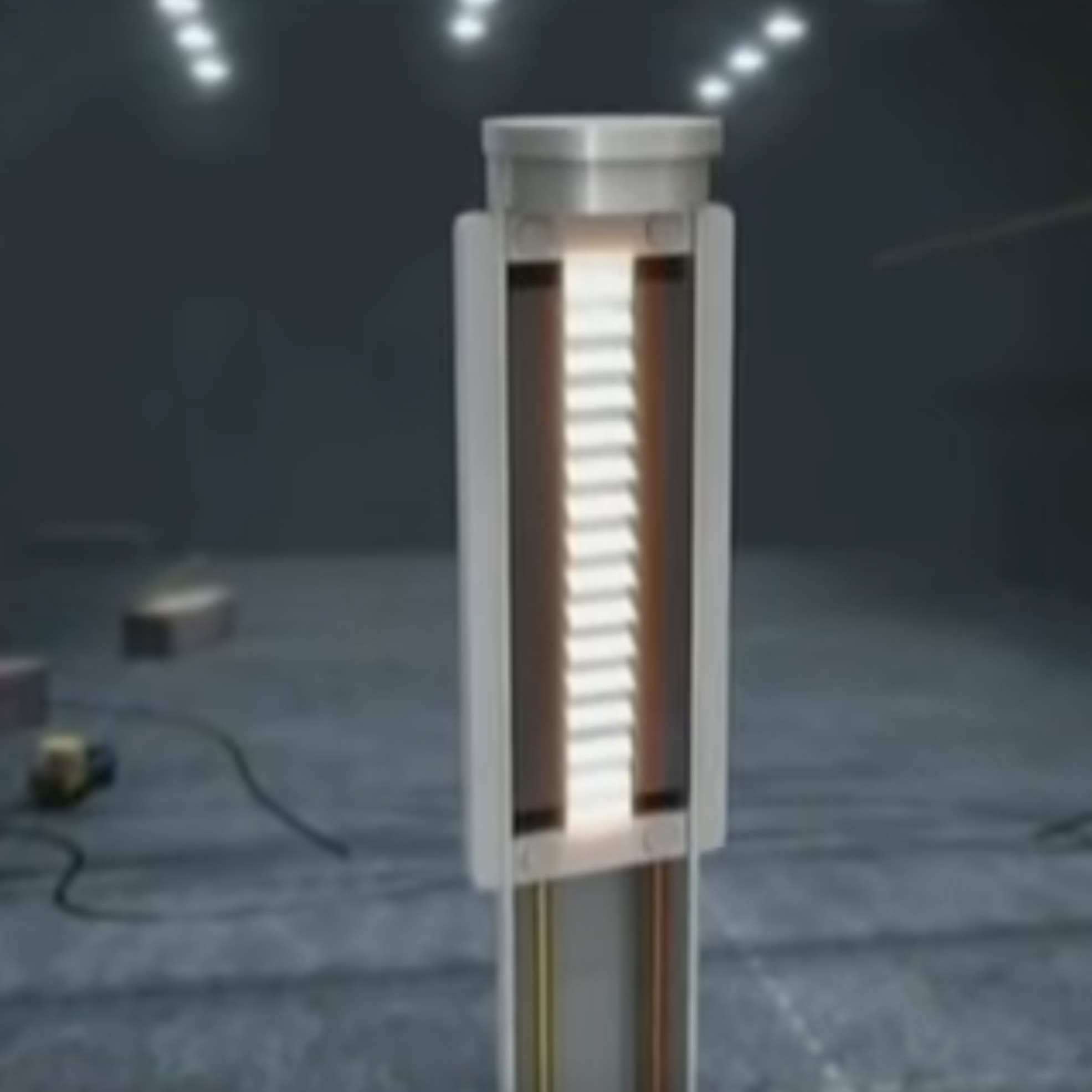

Anechoic Chamber Testing

One of the highlights of the tour was seeing that brand-new U87 go through its final acceptance testing. Each microphone is individually tested in an anechoic chamber, for all three polar patterns (Cardioid, Omni, Figure-8). Thinking back to the box of discarded parts on the Evolution line, I asked what the reject rate for U87s is. The answer: zero! Because if the mic isn’t right, it goes back into the shop to be fixed. At ~$3200 MSRP, the U87 doesn’t leave the factory until it is right.

The testing process is manual, but optimized for speed. Having a technician run in and out of an anechoic chamber to change the polar pattern twice for every mic just wouldn’t scale well, so the company has engineered a system whereby the technician can drive the whole process from the workstation outside the chamber. The mic is clipped onto a robotic arm, which drives it on a track through a small window into the chamber, to exactly the appropriate test position. A speaker within the chamber plays a 20Hz–20kHz sweep tone while an audio workstation tests the mic’s output, comparing it to the company’s acceptance standards. The frequency graph is plotted in realtime on a monitor.

Then the robotic arm retracts so that the technician can change the polar pattern (via the switch on the microphone) and repeat the test.

I was so fascinated by this that I asked if I could see it again from inside the chamber. The little room wasn’t big enough to stand in, but I squatted there with my camera in the dark and watched the mic shoot in from the left side. The speaker was somewhere behind me; I remember hoping the sweep tone wouldn’t deafen me, as I had both hands on my camera.

Needless to say, they had to retest the mic after I got out of the chamber. It had failed to meet the specified response, due to the unexpected presence of a 170lb fleshy acoustic baffle in front of the microphone.

|

|

|

|

Vintage Dynamics

I also got to see two of Sennheiser’s classic dynamics, the MD 421 and MD 441, being made. A woman at one workstation was gluing membranes by hand onto the MD 421 moving-coil cartridge. I asked a technical question about the cartridge, and my exceptionally accommodating host responded by peeling the membrane off of one of the completed cartridges to show me the parts underneath — after asking the installer’s permission, as she would have to replace it a moment later.

|

|

|

The Big Chamber

The very last attraction of the day, made quickly just before my host rushed me back to the train station, was a visit to the company’s largest anechoic chamber. It was a big space with a suspended wire floor, covered with deep wedges of acoustic absorption material on all 6 interior surfaces. Like all such chambers, it is unsettling to be in, because it sounds unlike anything else you’ve ever heard*. And maybe also because the floor moves up and down in exactly the way that most floors do not.

* except perhaps the “Alcatraz” room in Steve Albini’s studio.

|

|

|

One more measure of my nerd-dom: I would very much like to have one of these at home.

The train ride home

What impressed me most about my visit had nothing to do with microphones, or even technology. I was buzzing from everything I saw, to be sure, but what blew me away was the hospitality. I am deeply grateful to the staff of Sennheiser’s headquarters and factory for the VIP treatment. Even if I couldn’t keep that U87. 😉

The factory presented an awesome mash-up of old world, manual processes and brand-new automation technology. It was a lesson in finding the right solutions for wildly different needs: modernizing and automating where appropriate, but retaining the staff of craftsman for the processes that demand such attention.

I should mention that a year after my visit, the factory played host to a camera crew from a TV show called “How It’s Made.” You guessed it, they filmed the U87 manufacturing process. The shots in the video are all cropped very tight on the various parts being made, and as such the video depicts a fairly cold and impersonal process — which is not the feeling I got from the place at all. Still, if you liked the photos here, you’ll like the video too. See it here: Making of a U87.

I should mention that a year after my visit, the factory played host to a camera crew from a TV show called “How It’s Made.” You guessed it, they filmed the U87 manufacturing process. The shots in the video are all cropped very tight on the various parts being made, and as such the video depicts a fairly cold and impersonal process — which is not the feeling I got from the place at all. Still, if you liked the photos here, you’ll like the video too. See it here: Making of a U87.

I have a standing invitation from my pals at Shure to visit their facilities, and I hope to do so soon. Any other manufacturers willing to tolerate a nosy guest for a day, let me know!

If you don’t happen to operate a major microphone manufacturing facility, you could still help me out by “liking” and sharing this article. See the FB and G+ buttons in the sidebar at the top of the page. Many thanks!

Posted in Microphones, Music Business, Photos | 16 Comments »

Eric Beam

August 2nd, 2012 at 10:51 am

Great read.

Nice to see that it’s still very much a hands on build process.

rene

August 2nd, 2012 at 4:54 pm

great writeup. loved every word and photo!

chris porro

August 3rd, 2012 at 12:23 am

do they give “journalist cards” to anyone with a blog? i’d like one.

did they tell you what they were shooting for on the u87 in the test chamber? wonder if it would be worth doing transient tests as well as the freq ones.

Brian

August 3rd, 2012 at 5:25 pm

Reads like a once in lifetime experience Matt, the whole process is just awesome! Cheers bloke!

eric kerns

August 9th, 2012 at 2:02 am

I Will Share as i was thrilled that you shared with us !

Andrew

August 9th, 2012 at 6:15 am

Great article, I found it very informative.

However, I’m curious to know what benefit you would derive if I “liked” the article rather than just liked it. Isn’t FB’s share price sinking like a stone because it offers little or no real commercial benefits to its users?

Luis Fernando

August 10th, 2012 at 10:05 am

Great photos!

Christopher Sauter

August 10th, 2012 at 11:08 am

this was AWESOME.. read the whole thing, loved the pictures… It helped me understand the capsule of a microphone so much more now… thank you!!

Victor Mason

August 10th, 2012 at 4:45 pm

You did superb job, I felt like I was there! Very impressive and that factory proves why they are worth the money without a doubt!

Adrian Murphy

August 13th, 2012 at 5:11 pm

Wow, you really pulled back the curtain on Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory here! Great stuff. Would love to tour the Sennheiser headphones division…

Mike McHenry

August 23rd, 2012 at 11:19 am

Love sennheisers. Thanks for posting the tour, reaching back into my cabinet for my MD421 right now.

winny

August 24th, 2012 at 2:14 am

Great stuff, high res pics would be even better. There is also a really quirky studio tour of brauner on youtube worth watching.

dan

August 24th, 2012 at 3:16 pm

awe some, thanks. Please tour the Shure factory!

Pierre-Alexandre Sicart

September 15th, 2012 at 10:01 pm

Great tour, and great write-up: very clear, even to describe the production of the capsules.

Albert

February 17th, 2014 at 10:22 pm

Very interesting tour. Happy to understand why a capsule can be that expensive.

One question remains unanswered: do they build themselves the PCB and the electronic part? Does the absence of pictures of the process mean that they are made elsewhere (maybe out of Germany)?

Thanks again for your site!

Ed

February 23rd, 2014 at 3:31 pm

As I have been condescendingly told more than once: “You want the Neumann shimmer, you pay the Neumann price”